Articles

The Benner Cycle and the AI-Powered Economic Outlook for the next few years

The Benner Cycle: History and Phases

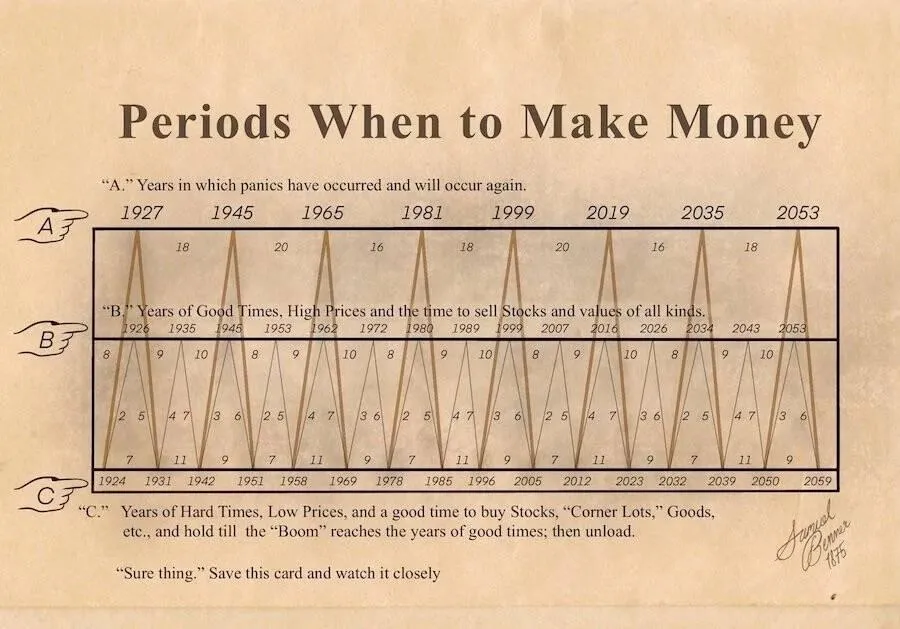

Samuel Benner, an Ohio farmer, published Benner’s Prophecies in 1875 after being wiped out by the Panic of 1873. In his studies, Benner identified recurring economic “Good Times,” “Hard Times,” and “Panic” years. Good Times were boom years of high prices (ideal for selling assets), Hard Times were bust years of low prices (ideal for buying and holding assets for the next boom), and Panic years were acute financial crises when markets swung to irrational extremes. Benner’s 19th-century chart plotted these cycles decades into the future, marking alternating periods of prosperity and depression on a roughly repeating schedule.

Historical accuracy

Remarkably, many of Benner’s predicted turning points have aligned with real events. For example, the cycle anticipated the 1929 Wall Street Crash and Great Depression, the 2000 dot-com bust, and the 2008 global financial crisis, among others. While not exact in timing, Benner’s pattern of major “panic” downturns roughly every ~16–18 years has often coincided with these landmark crises. His “Sure thing” cycle card proved “close to perfect” for over a century, capturing the rhythmic shifts in market psychology (from greed to fear) that drive booms and busts. Analysts have noted that the Benner Cycle’s ebb and flow mirrors market sentiment cycles, lending it an almost self-fulfilling credibility.

2024–2030 cycle outlook

According to Benner’s timeline, the mid-2020s mark a crest of “Good Times” before a downturn. In fact, updated forecasts based on Benner’s cycle suggest we are in a favorable boom period from 2024 through 2026, followed by a shift into unfavorable years from ~2027 until the early 2030s. This implies strong growth and high asset prices in the next couple of years (“sell” by 2026) and a recessionary phase or market “panic” unfolding around 2026–2027 that leads into multi-year economic hardship into the late 2020s.

Benner’s cycle indicates “Good Times” (growth phase) through the mid-2020s, peaking around 2025–2026, then “Hard Times” (downturn phase) from ~2027 into the early 2030s. The timeline above illustrates these projected phases. The question is how emerging trends like the current AI boom might fit into this pattern.

Notably, this cycle forecast aligns with other analyses: for instance, solar activity and even financial tradition point to a major market peak by 2025 and a downturn by 2026–2032. The presence of a transformative technology boom (artificial intelligence) during the predicted “Good Times” raises the stakes – and offers a test of the cycle’s predictive power. Below, we examine expert predictions on AI’s impact through 2027 and assess how they correspond to Benner’s “Good → Panic → Hard” sequence.

AI-Driven Business and Productivity Trends

Businesses are currently riding a wave of AI-driven optimism, investing heavily in automation and generative AI tools to boost productivity. In 2024, 64% of top CEOs worldwide named AI as their number one investment priority. Many firms report immediate efficiency gains: a recent survey of U.S. financial companies found about 20% average productivity improvement in software development and customer service after deploying generative AI tools. Across industries, generative AI is being piloted to write code, draft content, assist customer support, and more – often accelerating tasks by 20–30% for early adopters. These early productivity boosts have led companies to pour more resources into AI; 63% of CEOs expect returns on AI investments within 3–5 years (i.e. by 2027–2028). In short, AI is viewed as a key driver of business growth and competitive advantage in the mid-2020s.

Broader economic impact:

Analysts project that AI’s effect on productivity will become macro-evident over the next decade. Goldman Sachs researchers forecast that by around 2027, AI will begin measurably lifting U.S. GDP growth. In a baseline scenario, widespread AI adoption could add ~1.5 percentage points to annual productivity growth in advanced economies over 10 years. One estimate holds that generative AI tools could ultimately raise global GDP by 7% (nearly $7 trillion) over a decade, and boost labor productivity growth by ~1.5% per year. Similarly, McKinsey research finds generative AI could contribute an additional $2.6 – $4.4 trillion in economic value annually across industries once fully implemented – roughly a 15–40% increase on top of the impact of other digital technologies. In sectors like customer operations, software engineering, and marketing, AI is unlocking major efficiencies, which in aggregate may significantly raise output per worker in the coming years.

Benner Cycle alignment:

These trends are consistent with a “Good Times” boom. The mid-2020s economy is seeing strong corporate earnings and stock market highs, fueled in part by AI enthusiasm. Indeed, the S&P 500 and tech-heavy NASDAQ surged to record levels by 2023–2024, led by AI-related stocks (e.g. chipmakers). This exuberance mirrors prior tech booms (the late-1990s dot-com era) and reinforces Benner’s notion of peaking optimism before a downturn. Many CEOs are bullish that AI will drive efficiency, innovation, and growth in the near term – a sentiment fitting for the cycle’s prosperous phase.

However, the cycle also warns of Panic ahead, and there are growing voices of caution. Market observers note “echoes of the dot-com bubble” in the current AI-driven rally, warning it could end “with an epic crash” akin to 2000. In fact, one research firm predicts the AI-fueled stock bubble may burst around 2026, wiping out some of the recent valuation gains. Such a correction would mark the transition from Benner’s Good Times to Hard Times. If that occurs, the very optimism and high investment we see now (AI startups at record valuations, companies rushing to adopt AI) might give way to a shakeout – reinforcing the cycle’s timing. On the other hand, if AI’s productivity boost is so powerful that it prolongs growth or softens a downturn (e.g. by lowering business costs), it could moderate the severity of Hard Times, partially contradicting the expected cycle. We will revisit this interplay as we discuss jobs, sectors, and policy responses.

Job Displacement and Creation Forecasts

The rapid advancement of AI has sparked intense debate about its impact on employment. Global forecasts over the next 3–5 years expect substantial job churn – both losses and gains – due to AI and automation. According to the World Economic Forum, by 2027 about 23% of current jobs will have changed (in terms of tasks or skill requirements), as 83 million roles are eliminated and 69 million new ones emerge. This implies a net loss of ~14 million jobs worldwide (roughly –2% of global employment) in the mid-term. Similarly, Goldman Sachs analysis found that generative AI could “expose” approximately 300 million full-time jobs globally to automation of some degree. In the U.S., about two-thirds of occupations could be partly automated by AI, with 25–50% of the workload in those jobs potentially replaced. Roles involving routine data processing, administrative and some customer service functions are seen as most at risk in the near term, along with repetitive manual jobs (thanks to robotics).

Broader economic impact:

Analysts project that AI’s effect on productivity will become macro-evident over the next decade. Goldman Sachs researchers forecast that by around 2027, AI will begin measurably lifting U.S. GDP growth. In a baseline scenario, widespread AI adoption could add ~1.5 percentage points to annual productivity growth in advanced economies over 10 years. One estimate holds that generative AI tools could ultimately raise global GDP by 7% (nearly $7 trillion) over a decade, and boost labor productivity growth by ~1.5% per year. Similarly, McKinsey research finds generative AI could contribute an additional $2.6 – $4.4 trillion in economic value annually across industries once fully implemented – roughly a 15–40% increase on top of the impact of other digital technologies. In sectors like customer operations, software engineering, and marketing, AI is unlocking major efficiencies, which in aggregate may significantly raise output per worker in the coming years.

Benner Cycle alignment:

These trends are consistent with a “Good Times” boom. The mid-2020s economy is seeing strong corporate earnings and stock market highs, fueled in part by AI enthusiasm. Indeed, the S&P 500 and tech-heavy NASDAQ surged to record levels by 2023–2024, led by AI-related stocks (e.g. chipmakers). This exuberance mirrors prior tech booms (the late-1990s dot-com era) and reinforces Benner’s notion of peaking optimism before a downturn. Many CEOs are bullish that AI will drive efficiency, innovation, and growth in the near term – a sentiment fitting for the cycle’s prosperous phase.

However, the cycle also warns of Panic ahead, and there are growing voices of caution. Market observers note “echoes of the dot-com bubble” in the current AI-driven rally, warning it could end “with an epic crash” akin to 2000. In fact, one research firm predicts the AI-fueled stock bubble may burst around 2026, wiping out some of the recent valuation gains. Such a correction would mark the transition from Benner’s Good Times to Hard Times. If that occurs, the very optimism and high investment we see now (AI startups at record valuations, companies rushing to adopt AI) might give way to a shakeout – reinforcing the cycle’s timing. On the other hand, if AI’s productivity boost is so powerful that it prolongs growth or softens a downturn (e.g. by lowering business costs), it could moderate the severity of Hard Times, partially contradicting the expected cycle. We will revisit this interplay as we discuss jobs, sectors, and policy responses.

Crucially, however, “exposed” does not mean “eliminated.”

Historical precedent suggests many workers will adjust and new jobs will offset losses. As Goldman economists note, most jobs are only partially automatable and will be complemented rather than fully replaced by AI. For example, AI may take over tedious tasks, allowing employees to focus on higher-value work. Furthermore, technology-driven innovation creates entirely new roles – over 85% of net employment growth in the past 80 years has come from new occupations (e.g. software developers, digital marketers) that arose after previous tech revolutions. Many experts therefore project that while certain job categories (like data entry clerks, routine accounting, and assembly line workers) will decline, demand will surge for others: AI specialists, data analysts, software engineers, as well as roles in training AI, ethics, and maintenance. The WEF finds that roles in AI/Machine Learning, big data, and information security are among the fastest-growing, with AI professionals projected to increase ~40% by 2027. Meanwhile, jobs requiring uniquely human skills – in healthcare, education, and creative fields – are expected to grow as well.

Workforce outlook (2024–2027):

We can anticipate an accelerated need for reskilling and transition support. Employers estimate that 44% of workers’ core skills will need to change by 2027 to adapt to AI and other trends. This has led to a push for upskilling programs. For instance, companies like IBM and Amazon have launched major retraining initiatives to fill AI-related roles with internal talent instead of layoffs. Notably, a majority of business leaders remain optimistic that AI will be a net job creator in their firms. In one survey, 49% of companies expected AI to actually create new jobs and tasks, while only 23% expected a net decrease in jobs. Many CEOs even plan to increase hiring despite AI – in KPMG’s 2024 outlook, 92% of CEOs said they intend to boost headcount over the next three years. They view AI as a tool to augment their workforce’s productivity, not necessarily shrink it in the short term. For example, AI might enable smaller teams to accomplish more, but businesses also need new talent (data scientists, AI engineers) to implement and manage these systems.

Benner Cycle alignment:

The current labor market still reflects “Good Times” conditions – unemployment in the U.S. and many countries has been low, and companies are hiring or retraining staff to leverage AI rather than immediately slashing jobs. This fits with the late-cycle economic strength (high labor demand) that Benner’s cycle would predict before a peak. As we approach the anticipated Panic/Hard Times phase (late 2020s), however, job displacement concerns could intensify. If an economic downturn hits around 2026–2027, it may be exacerbated by automation: companies facing cost pressures could turn even more to AI and robots, potentially accelerating layoffs in routine jobs during the recession. That scenario would reinforce the Benner pattern – a sharp spike in unemployment (Panic) followed by several years of painful readjustment (Hard Times). Indeed, policy think-tanks warn of a possible “AI shock” to the labor market in the next downturn, where workers without updated skills face harder unemployment. Alternatively, if AI-driven industries continue to create new jobs quickly (e.g. in software, green tech, etc.), this could provide a cushion during Hard Times, somewhat blunting the cycle’s impact on overall employment. Policymakers are already focusing on worker transitions to try to ensure the next bust doesn’t become a lasting unemployment crisis. The true test will be whether the jobs created by AI (and other emerging industries) arrive in time and at sufficient scale to absorb those that AI displaces – particularly if Benner’s timing of a late-decade recession proves accurate.

Job Displacement and Creation Forecasts

AI’s impact will not be uniform across sectors – some industries are being revolutionized, while others adopt AI more gradually. Below is a summary of key sector transformations expected in the next few years and how they tie into economic trends:

Across other sectors: High tech itself (software, internet services) is obviously booming with AI – driving stock market gains and venture capital investment in the current cycle. Retail is using AI for demand forecasting and inventory optimization, while transportation sees early AI in autonomous vehicles and logistics routing. Agriculture is getting AI-driven precision farming. These innovations can increase productivity and output, theoretically countering inflation and supporting GDP – but they also can overshoot (e.g., over-investment in unproven tech, reminiscent of dot-com excess).

Benner Cycle alignment: During the Good Times phase (now), we observe that tech-centric sectors (like finance, tech, manufacturing) are reaping outsized benefits from AI, contributing to economic growth and bubbly equity valuations (e.g., the tech sector now comprises ~32% of the S&P 500’s value, the highest since 2000). This concentration of wealth in tech mirrors the late-1920s (radio/automobile boom) and late-1990s (internet boom) eras that preceded past crashes, reinforcing the cycle’s warning signs. If a Panic hits around 2026, it may be precipitated by one of these sectors – for example, a sharp correction in over-hyped AI tech stocks or a failure of some highly AI-leveraged financial institution. In the subsequent Hard Times, we would likely see consolidation: weaker tech firms failing (as happened after 2000), companies and governments focusing on applying the most valuable AI innovations to improve efficiency in a tight economy (e.g. using healthcare AI to cut costs, using automation to reduce expenses in manufacturing). Each sector’s AI adoption could thus evolve from “nice-to-have” during the boom to “must-have for survival” during a bust. If the cycle instead turns out less severe, it could be because AI improvements in sectors like healthcare, energy, and food mitigate some economic pain (for instance, AI helping to lower commodity costs or improve productivity even amid a downturn).

Macroeconomic Implications of AI (GDP, Productivity, Markets)

On the macroeconomic level, the AI revolution introduces both tailwinds and potential pitfalls over the next few years. On the positive side, higher productivity from AI should expand economic capacity and growth. As noted, widespread AI adoption could boost long-run global GDP by several percentage points. For the United States, AI is expected to start adding 0.4 percentage points to annual GDP growth by around 2027 and similar increments in other developed markets. By the early 2030s, we could see AI contributing a meaningful share of GDP growth, akin to past general-purpose technologies (electricity, computers). Labor productivity – which has been sluggish in the 2010s – might accelerate as companies produce more output with augmented or smaller workforces. Estimates range widely, but McKinsey suggests generative AI + other tech could add anywhere from 0.5 to 3.4 percentage points to annual productivity growth, depending on adoption speed. Such gains, if realized, would be historically significant (potentially akin to the productivity jump of the 1990s tech boom). In theory, higher productivity also means lower inflationary pressure, since supply capacity grows – a critical factor if we enter a downturn (it could make any recession milder than otherwise).

However, there are complex dynamics to consider:

In summary, AI adds a new ingredient to the traditional business cycle. It has the potential to reinforce the boom (by driving growth higher, as we see now) and to amplify the bust (if a speculative bubble and structural job shifts occur). The Benner Cycle’s prediction of a downturn around 2026–2030 could very well coincide with a period of adjustment to AI: productivity gains might lag initial hype (a “productivity J-curve”), meaning we have an investment surge now but the full economic benefits not visible until after 2027. That scenario implies a few years of disappointment – aligning with Hard Times – before AI’s promise truly pays off in the 2030s (a new boom). Such a pattern would closely mirror past tech cycles (the late 1960s boom in space/computers followed by the 1970s stagnation, or the dot-com boom-bust and eventual tech-driven growth of the 2010s). If instead AI quickly yields obvious gains and avoids a hype bust, the economy might evade a severe Benner downturn this round, thus breaking the historical cycle by entering a more productivity-led steady expansion. At least for now, evidence points to a classic boom/bust dynamic (AI hype boom, potential correction), but this is a pivotal space to watch.

Government and Corporate Responses to AI Disruption

Recognizing the profound changes AI may bring, both governments and businesses are actively preparing responses – which will influence how smoothly the economy navigates the next few years.

Government policy actions:

Policymakers are balancing support for innovation with managing AI’s risks. In 2023–2024 there has been a flurry of regulatory initiatives: the European Union passed the landmark AI Act in 2024, the world’s first comprehensive AI law, which sets rules according to AI systems’ risk levels (e.g. stricter requirements for AI in critical areas like hiring or healthcare). This EU law, akin to how GDPR set a global standard, is expected to influence regulations in other countries. China has also implemented regulations (e.g. rules for generative AI services) to control content and ensure security. In the U.S., there isn’t yet a single AI law, but the government has leaned on a mix of guidance and executive action. In October 2023, the White House issued an Executive Order on “Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI,” which, among other things, requires developers of advanced AI models to share safety test results with the government and sets standards for AI system security and bias reduction. Federal agencies are designating Chief AI Officers and drafting AI risk management frameworks. Additionally, the U.S. government brokered voluntary commitments from leading AI firms (OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, etc.) to implement measures like algorithmic testing, watermarking of AI-generated content, and information sharing on AI safety – aiming to mitigate dangers like misinformation and misuse.

As we approach 2025–2027, more government responses are expected: many nations are investing in AI research and education (for example, funding STEM programs, AI labs, and workforce retraining). The UK hosted a global AI Safety Summit in 2023 and is establishing an AI Safety Institute, reflecting a focus on longer-term existential risks as well. International bodies (OECD, G7, United Nations) are coordinating on AI ethics guidelines and standards. In a Hard Times scenario, one might anticipate even stronger government intervention – e.g. if AI-driven unemployment spikes, there could be pressure for job protection laws or universal basic income trials; if an AI-related financial panic occurs, regulators would likely impose stricter oversight on AI in finance. Indeed, historically, regulation often tightens after crises, so a 2027–2030 downturn might prompt the formalization of many currently voluntary AI governance practices into law (much as the 1930s and post-2008 periods yielded major financial reforms). For now, governments are trying to get ahead of the curve to ensure AI’s benefits can be realized without sparking public backlash or instability, thereby attempting to smooth out the transition that coincides with the Benner cycle timeline.

Corporate strategies:

Companies, for their part, are not waiting idly. As noted, CEOs are heavily investing in AI capabilities – but they are also mindful of the risks and responsibilities. A majority of executives (61% in one survey) acknowledge ethical and governance challenges as a difficult aspect of AI implementation. Thus, many large firms have set up internal AI ethics boards and are developing guidelines for responsible AI use (to avoid biased algorithms or breaches of privacy). Businesses are also focusing on their workforce: encouraging a culture of continuous learning so employees can work alongside AI. In KPMG’s global CEO survey, the top cited benefits of AI adoption included “upskilling the workforce for future readiness,” improved efficiency, and innovation. This indicates companies see human capital development as central to their AI strategy, not just cost-cutting. For example, consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers announced it would invest $1 billion in training its employees on AI tools. Many firms have rolled out AI training modules or provided access to platforms like Coursera to help staff gain AI literacy.

Corporations are also collaborating with governments and academia on solutions – e.g. partnering on apprenticeship programs for data science, or contributing to policy discussions on re-skilling and safety. Notably, despite fears, most CEOs do not intend to make drastic layoffs purely because of AI in the short term: 76% of top CEOs surveyed believed AI will not fundamentally reduce headcount at their company. Instead, they foresee AI automating tasks, changing roles rather than eliminating them wholesale. This managerial stance (if maintained) could soften the labor market impacts that Benner’s Hard Times phase might otherwise bring. Of course, if a severe recession hits, cost-cutting could override these intentions – but the current approach is to use AI to augment teams and drive growth, not just as a replacement tool.

Another corporate response worth noting is in the market and R&D domain: Tech companies are in an arms race to develop more powerful AI (e.g. GPT-5, new image generators) which they promise will unlock even greater economic value. This race contributes to the boom atmosphere now. But these same companies are lobbying for thoughtful regulation to avoid a public trust crisis that could hurt AI adoption. Many have voluntarily implemented AI usage policies (for instance, restricting employee use of public AI tools for sensitive data) and are exploring ways to verify AI outputs (watermarking) to combat deepfakes and fraud. In financial services, firms are working with regulators to ensure AI models in lending don’t violate fair-lending laws, etc. How businesses govern AI internally in the next few years could greatly influence whether the technology’s rollout causes economic disruptions or smooth progress.

Benner Cycle alignment: The collective response by government and industry can either cushion or exacerbate the cycle. In optimistic terms, proactive policies (like retraining programs, prudent regulation to prevent AI risks) could alleviate some Hard Times pain, making the downturn less severe than history might predict. For example, if governments successfully implement reskilling at scale, workers displaced by AI might more quickly transition to new jobs, keeping unemployment lower than it would be otherwise. If regulators preemptively curb the most speculative excesses (say, ensuring AI startups adhere to risk management, preventing an AI-fueled credit bubble), we might avoid a catastrophic panic. These efforts would weaken the reinforcement of Benner’s cycle (i.e. the downturn might be milder or shorter).

On the other hand, missteps in policy – such as over-regulating too early (strangling innovation and growth) or under-regulating (leading to a scandal or crash that shatters confidence) – could amplify the cycle. A stark scenario: imagine no safety nets for displaced workers; unemployment surges in 2027, public anger rises, and protectionist measures follow, further slowing the economy – that would deepen Hard Times and very much echo past cycle downturns. Alternatively, consider if the current voluntary AI governance fails and there’s a major AI-related crisis (like a widespread cybersecurity breach or financial algorithm failure). The loss of trust could trigger the “Panic” Benner foresaw, as investors and the public recoil from technology. Government would then clamp down heavily, perhaps overcorrecting (much like Sarbanes-Oxley and other post-bust regulations did), which could stifle the early stages of the next recovery.

At present, the pattern of boom-time laissez-faire vs. bust-time intervention appears to be repeating: during this boom, regulation is relatively light-touch and innovation-friendly (especially in the U.S.), but we see the groundwork being laid for more rules. Should the cycle turn, expect a swing towards heavier oversight of AI and stronger social safety policies – a pattern consistent with historical responses after panics.

Conclusion: Echoes of the Cycle in an AI Era?

In sum, our analysis finds that many dynamics of the current AI-driven economy align with the Benner Cycle’s phases. The exuberance and rapid growth of 2024–2025 – characterized by surging tech fortunes, full employment, and aggressive investment – strongly mirror the “Good Times” that Benner’s 150-year-old model predicted for this period. The fact that even the narrative parallels are similar (a revolutionary technology spawning optimism akin to past booms) lends weight to the cycle’s relevance. Experts caution that a “panic” or correction by 2026–2027 is a real possibility, whether due to an overheating market, inflation and rate hikes, or the bursting of an AI hype bubble. Such an event would neatly fit the cycle’s timing and would likely usher in the “Hard Times” Benner foresaw – a difficult adjustment period into the late 2020s where economies grapple with restructuring, perhaps high unemployment, and the need to integrate AI’s efficiencies in a more cost-constrained environment.

However, we also identify potential contradictions or moderating factors. AI’s unprecedented productivity gains could, in theory, extend the boom or soften the bust compared to past cycles. For instance, if AI helps solve demographic labor shortages or significantly lowers production costs, the economy might sustain growth longer without stoking as much inflation – possibly delaying a downturn. Likewise, strong policy interventions (already in motion) might prevent the worst outcomes of a panic (for example, backstopping workers and stabilizing markets). It’s conceivable that the Benner Cycle’s 2020s dip could be shallower or shorter if AI rapidly boosts real economic output in the second half of the decade, providing a new engine of growth that counteracts the cyclical decline. In that case, the cycle’s “predictive power” would be partly defied by the transformative impact of technology.

The AI Revolution and Economic Cycles

In reality, though, history shows that major technological revolutions do not prevent cycles – they often exacerbate them in the short run (think of railroads in the 1840s, electrification in the 1920s, or dot-com internet in the 1990s, all accompanied by manias and crashes), even as they raise long-run potential. The AI revolution appears to be following a similar arc. So far, it is reinforcing the classic pattern: extraordinary optimism, rapid expansion, and likely soon, a moment of truth when exuberance meets reality. If the Benner Cycle holds, we are on the cusp of that inflection. The period of 2024–2030 could well validate this 150-year-old cycle once again – with AI as a catalyst playing a starring role in both the boom and the adjustment to follow. By closely monitoring how AI impacts productivity, jobs, and policy in the coming years, we’ll also be watching the age-old drama of the economic cycle unfold in a modern form. The intersection of Benner’s cyclic wisdom and AI’s transformative promise will shape whether the next few years are remembered as a smooth evolution or a volatile revolution in our economy.

Sources

Benner’s original cycle and interpretations;

analyses of historical alignment;

AI impact forecasts from Goldman Sachs, McKinsey, World Economic Forum, and others as cited above;

policy updates from WEF and government releases.